Still, the point is that it’s not genre-defying any longer and has entrenched itself as one of the many methods that poetry can bridge the insubstantial of thoughts/emotions with the tactile such as someone else’s work, a newspaper, even an old poster or piece of trash can be infused with message or newfound symbolism.

Pop culture is an obvious target for recontextualization because it’s so rife with imagery, so in love with its own paradoxically meaningless necessity. It provides so many tropes that bring forth shared meanings that it’s just begging for someone to turn it on its head. One area though that seems to be untouched by the busy hands of the recontextualizer (now there’s a noun), is comics. Why not before? Perhaps the simplicity or implied shallowness of the funnies isn’t a worthwhile target. Or perhaps, new technologies (cough, cough, photoshop) are only now available to the average user to play around with graphic files.

Whatever the reason, comics are certainly now coming under the microscope in a big way. There are numerous webpages popping up with users delighting in the reconstruction/deconstruction of their favourite comics.

For example:

The comic recontextualizer

Truth and Beauty Bombs

Two of the most popular targets are Bill Keane’s Family Circus and Jim Davis’s Garfield, two comics emblematic of the old guard, ala Snoopy or Dagwood. Doubly funny is the fact that what probably makes these comics such a target isn’t just the core content, but the willingness of the creators to battle with the recontextualizers.

For example, take a look at this: Bill Keane speaking to recontextualizer

Because Family Circus’ ideological footing is so firmly set in one place, it’s an easy push-over. The obviousness of Bill Keane’s rightist missives make it a pendulous soapbox in the swirling winds of popular culture.

Garfield, on the other hand, absolves itself of any opinion for the sake of commercial universality. By Jim Davis’ own admission, Garfield’s vision statement is summed up with the zeroing mantra of “no comment.” Like any great politician, Jim Davis says a lot without actually saying anything.

Asides from artistic considerations, Garfield is basically the same as it’s always been, and some would say, including myself, that its tired conceits grew out their welcome at least a decade ago. The shark was jumped; the shark was passed; the shark is a mere speck on the horizon.

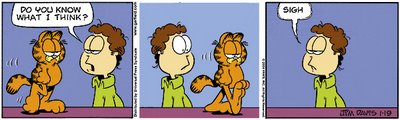

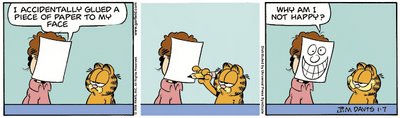

Recontextualizing has an odd effect on Garfield that’s difficult to duplicate with other comics. Garfield relies on the tenuous reality that Jon, a lonely bachelor, can interact with his witty cat. Garfield is the straight man to Jon’s anxieties; the super-ego to Jon’s frantic id. When Garfield’s commentary is removed, a disturbing reality sets in; Jon in all his neuroses is talking to a cat, is rationalizing to a cat, is pleading the meaning of his existence to a cat.

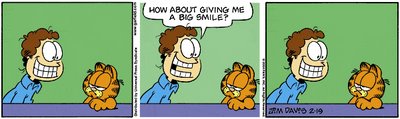

The effect is both hilarious as below:

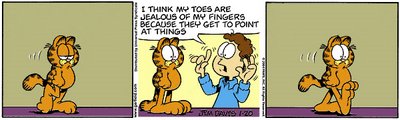

Or, sadly profound like such:

Where recontextualizing Family Circus is a rote exercise in inverting Keane’s wishes for a bygone time (that never really existed), Garfield takes a new freshness, a displaced meaning where Jon’s anxieties are magnified by the lack of another speaker. Where changing Keane’s work is basically like making fun of a grandfather and his wishes for the “good old days,” changing Davis’ work adds real pathos and absurdity that actually exists in life.

By making Garfield “a cat” the comic takes on a new existential tone full of the ambiguities and disheartening reality of loneliness. It’s strangely funning, sometimes making a new joke altogether, or other times cutting out the extraneous dialogue to deliver the joke in its purest form. It’s strangely funny because it’s kind of real, while still being delivered in the “un-real” artifice that is comics.

Who knew that comics were hardly a laughing manner?

No comments:

Post a Comment